Collectible Autographed and Dated “Whistling Bird” Teakettle by Michael Graves (1934 - 2015) | Mid Century Artifact

All our items ship free in the US

Dimensions: 8-1/2”dia x 9-0”h

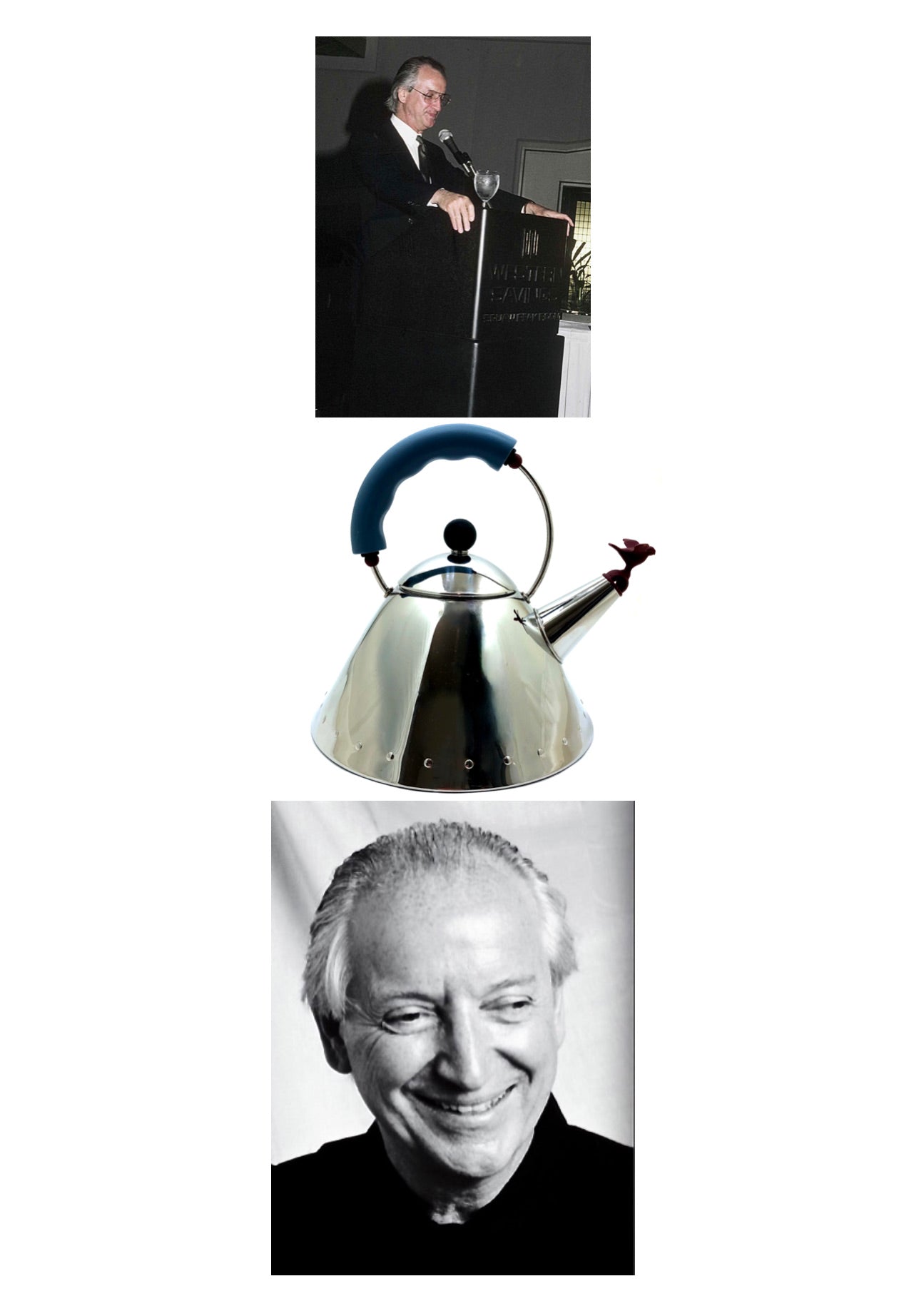

Michael Graves, one of the twentieth century's most renowned architects and product designers designed three teakettles. Grave was brought to Arizona State University, School of Design to lecture in 1988 and to present his original sketchbook concepts and then move the design student body, and invited guests through his entire design process, including studies of various kettle details (spout, whistle, handles, etc.), color studies, dimensional drawings, renderings, study models, prototypes and finally, production pieces. The Eminent Scholar Lecture program established by Professor Wolf was intended to give the design majors a rare behind-the-scenes glimpse of the design process from original concept to production pieces ready for the consumer market.

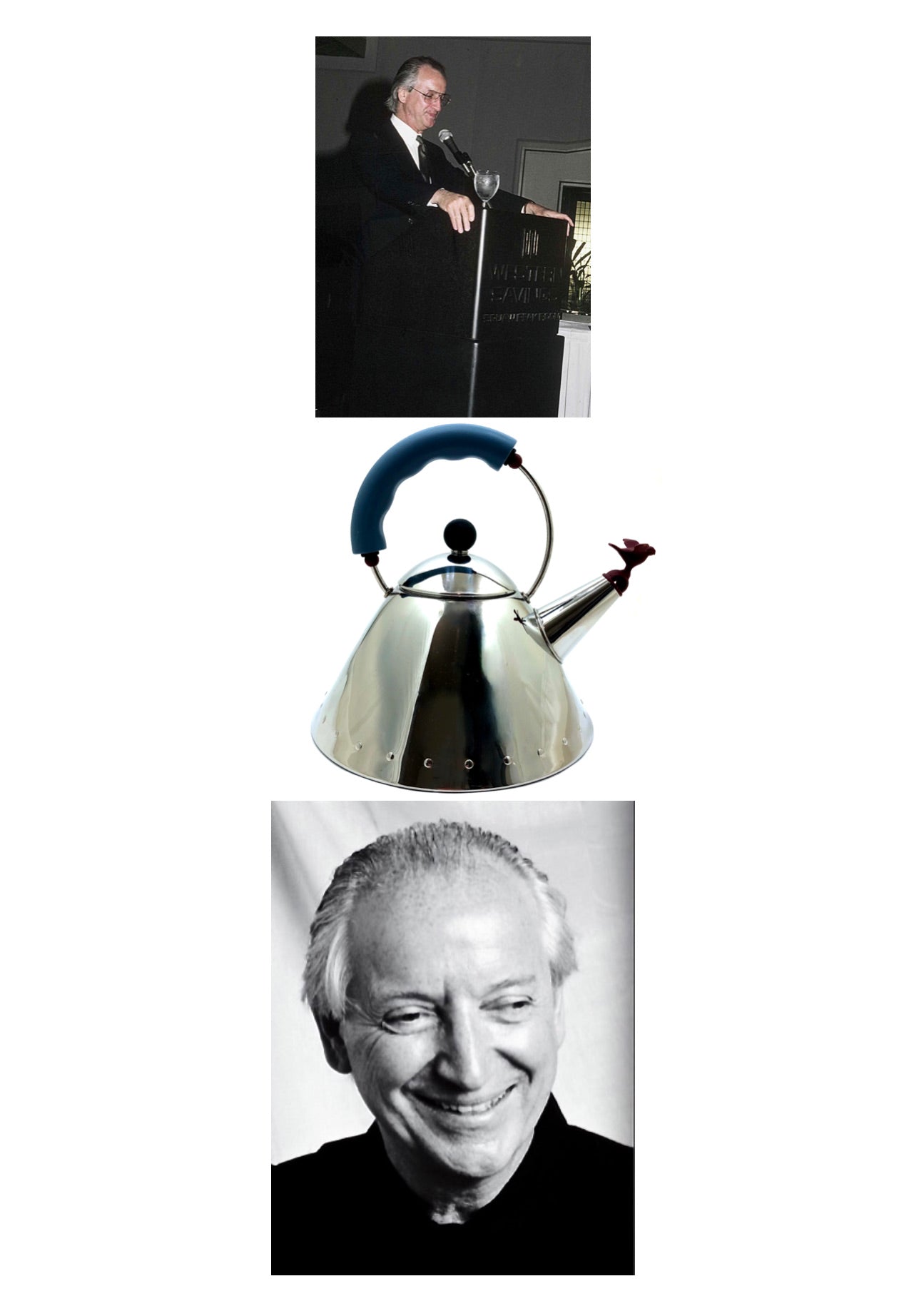

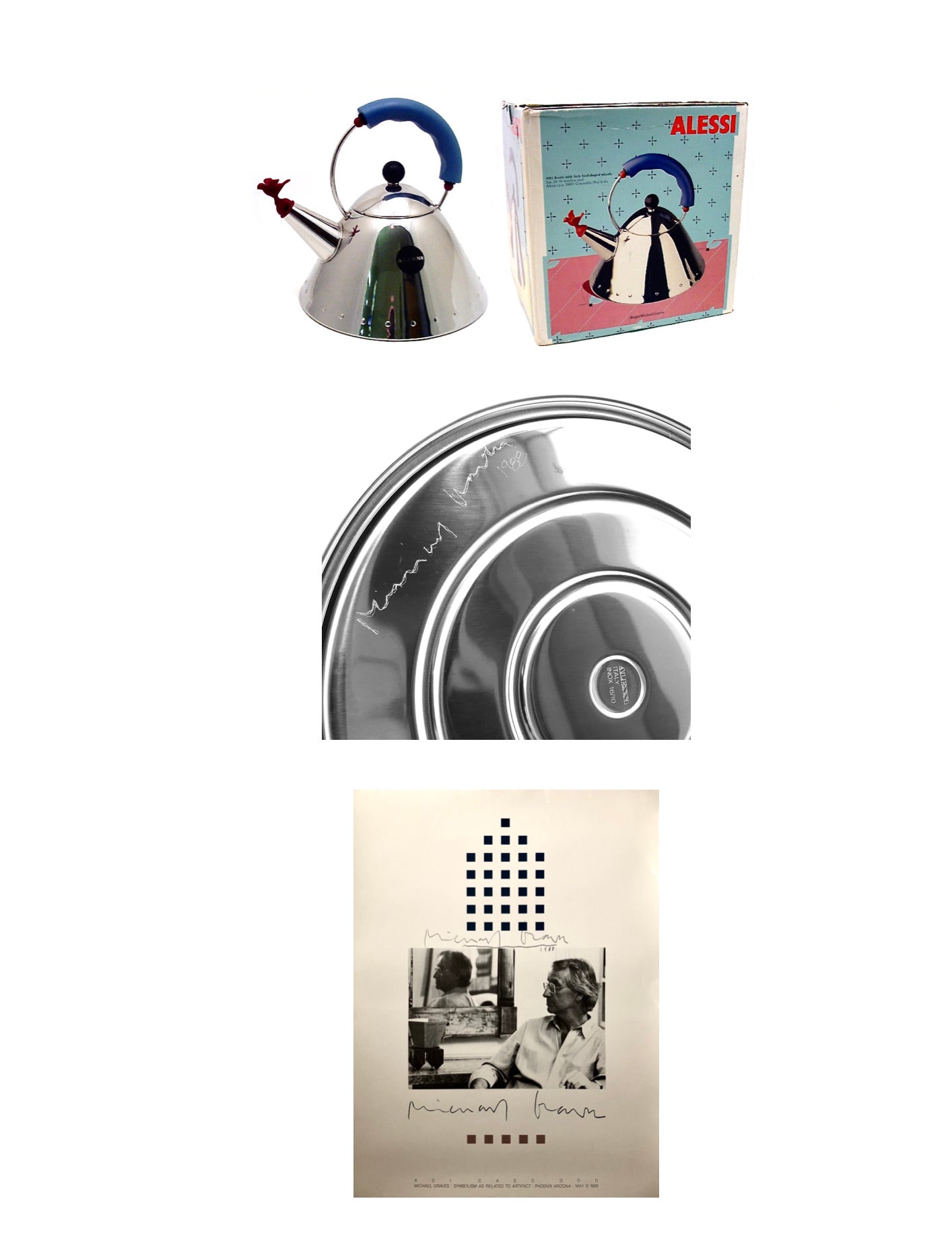

This original Alessi teakettle, (#9093) in 18/10 stainless steel has a blue handle and red bird-shaped whistle in PA resin at the end of the spout. This celebrated kettle sings when the water has boiled. This teakettle was a great success when it was introduced in 1985, and the focus of a meeting of design students in which he shared his philosophy on mass production methods, a combination that Michael Graves worked hard to achieve, applying his personal visual code which fused influences from Art Deco to Pop Art, and even the language of cartoons. In this offer to sell are included the following items (see images presented at the left of this page):

- Signed and dated (etched) TeaKettle

- The original box (commensurate with age)

- CD of the pre-interview w/Graves

- One pencil-signed poster announcing Graves's presentation.

Condition: The teakettle is in excellent, original condition with etched signature on the bottom of the piece. It is in its original box, (slightly tattered from age). The other items are in workable and visually excellent condition.

NOTE: Biographical Information on Michael Graves

Michael Graves was born in Indianapolis, Indiana, in 1934. He received his training in architecture at the University of Cincinnati and at Harvard University. Michael Graves was an American architect, designer, and educator, as well as principal of Michael Graves and Associates and Michael Graves Design Group. He was a member of The New York Five and the Memphis Group – and a professor of architecture at Princeton University for nearly forty years. In his private practice, Graves has completed a variety of projects including residences, multiple-family housing, medical facilities, museums, cultural facilities, and town plans. Following his own partial paralysis in 2003, Graves became an internationally recognized advocate of health care design.

He was awarded the Prix de Rome in 1960 and studied at the American Academy in Rome for two years. Graves is a Professor of Architecture at Princeton University, where he has taught since 1962. He has also served as Visiting Professor at the University of Texas, the University of Houston, U.C.L.A., and the New School for Social Research, and has lectured on his work throughout this country and Europe. He won five PROGRESSIVE ARCHITECTURE design awards, for his Rockefeller, Snyderman, Crooks, and Graves Houses for his Chem-Fleur Factory Addition and Renovation. In addition, he won the 1975 National Honor Award of the American Institute of Architects for his Hanselmann House. His work has been presented at the Museum of Modern Art in three exhibitions: “The New City”, in 1967; “The Architecture Studies and Projects,” in 1975. His drawings have also been exhibited at the Cooper Hewitt Museum and the Drawing Center. Graves was one of the six architects selected to present the United States at XV Triennale in Milan, Italy in 1973. His work has appeared in many periodicals as well as in several recent books: Five Architects, Architettura Razional, GA Houses, and The Language of Post Modern Architecture.

Additional Shared Experience: Published ICON Article and Background Information Documenting the TeaKettle Offered is the following article which is quoted as it appeared in ASID ICON Magazine, Summer 2015, and written by Dr. Beverly K Brandt professor emerita of Arizona State University.

My Dinner With Michael

Sitting next to Michael Graves at a banquet for graduating seniors in May 1988 was a highlight of my first year of teaching at Arizona State University. My department chair, Robert Wolf, had invited Graves on behalf of the Arizona Design Institute Eminent Scholar Lecture Program to serve as keynote speaker. His speech, titled “Symbolism and Its Relationship to Artifact,” was apropos. He had created his iconic teakettle with bird whistle spout a few years earlier and, in the process, had begun to revolutionize household products.

No longer content with spare, abstract modernism, Graves wanted to return the element of storytelling to building, interiors, and their contents.

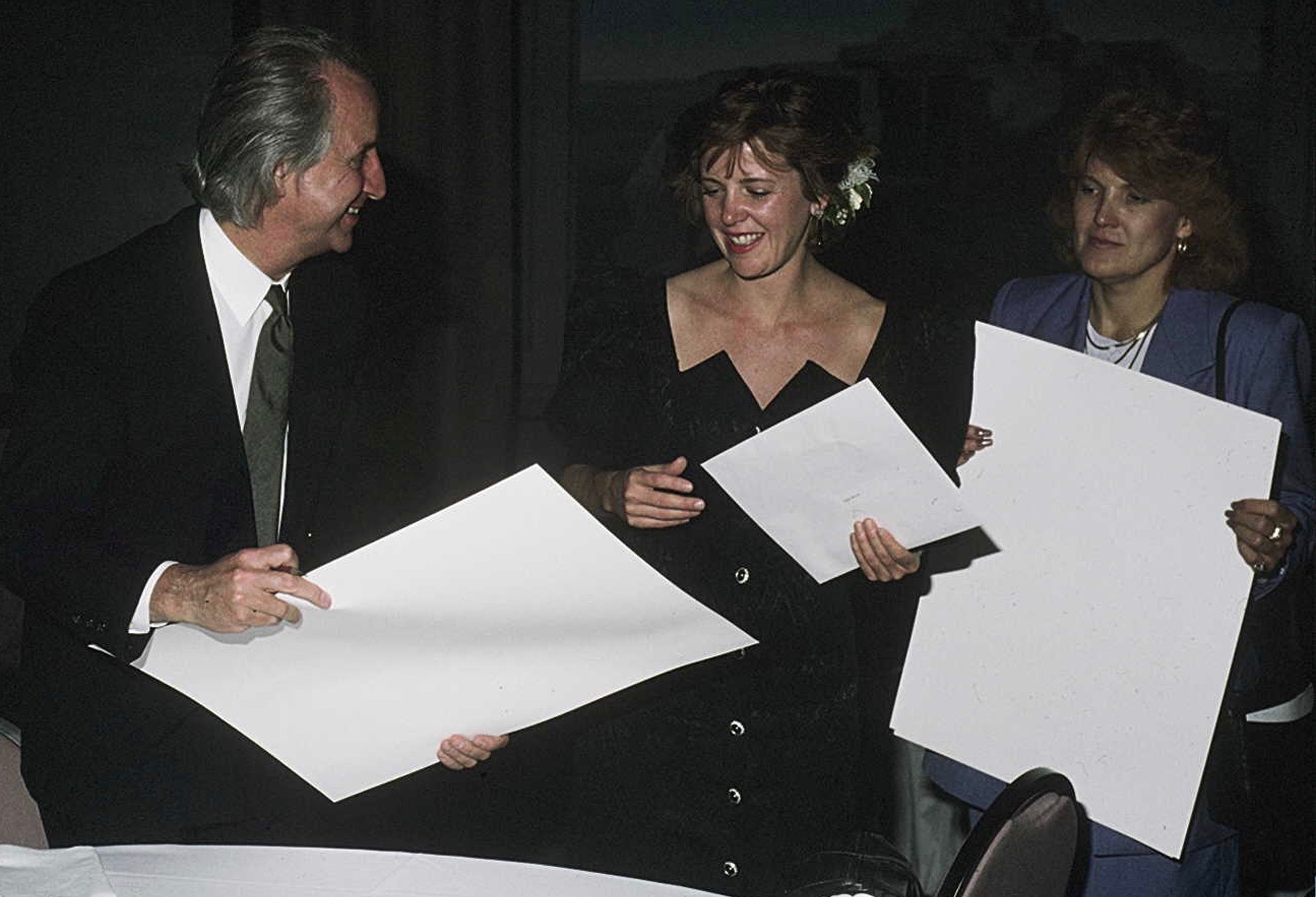

Wolf had purchased one of Grave’s teakettles, and he brought it, along with an electric engraving tool, to the banquet, hoping for an autograph. Graves obliged but confessed that the whole process was a bit awkward because he’d never before tired to write his signature on metal. He autographed posters and programs for a crush of students before and after his talk.

Graves had had a connection with Wolf being educator colleagues since the early 1980s and asked two of his students Lisa Hodge and Dixie Johnson conducted a telephone interview with Graves. This article relies in part on that interview, which was supplied by Wolf. Then, in 1985, Wolf asked Graves to meet with ASU faculty and students for which several product design students asked Graves to autograph their personal sketchbook, and Graves obliged with a fantasy drawing being published here for the first time.

Graves seemed to enjoy his visit to speak at ASU in 1988, commenting that he had lectured previously only at “private architectural schools.” That widening of his sphere of influence – from the rarified atmosphere of Princeton, Penn, Columbia, and Yale to the more common tier of the public institution – marked a parallel shift in his career. The 1980s was the decade in which Graves was designing for a large corporations and institutions. In the next decade, he launched a line of affordable products for the home, including his toilet brush for Target.

To democratize good design, Graves abandoned the modernist adherence to “design by subtraction” and embraced a post modernists’ preference for “design by addition.” Anything the modernist had removed, the postmodernist restored. This led to t he reintroduction of bright varied color, decorative motifs and patterns, myriad materials and faux textures, irregular shapes and those influenced by historical precedent, details borrowed from advertising or cartoons, and witty elements.

Grave’s embrace of a broader audience might be what drew him to collaborate with the Memphis Design Group – the impish, international collective of architects and designers – that held annual exhibition in Milan in the 1980s and turned the modernist design canon on its head. For Memphis, Graves produced his Plaza dressing table (1981), a combination of tiered art deco skyscraper., Hollywood starlet’s vanity, and comical startled face.

At the time of our dinner conversation, I was still a child of modernism, having been taught by academics who exposed the Miesian imperative “less is more.” I found Graves’ work to be fascinating and a bit appalling. It was only years later that I cam to appreciate his bold colors and patterns, quirky shapes, historicist references, and wit. Love it or hate it, postmodernism hits you in the gut. It made me re-evaluate every design theory and principle I held dear.

What do I remember most abut my conversation with Michael Graves? We joined our dinner companions at the head table, the first course arrived, and I asked him a question: “What projects are you working on right now that really excites you?” At that point the dialogue ended, and my dinner partner launched into an hour-long monologue, barely stopping to breathe or eat. He regaled me with tales of his current projects, which included his metropolis master plan for Los Angeles (never build), the Tajima office building (Tokyo), and Disney’s Hotel New York (Marne-la-Vallee, France.)

For my part, I smiled and urged, “tell me more” in between dainty bites, carefully not to dribble on my evening dress. I hope that Michael Graves had a wonderful time. I know I did. As soon as dinner concluded, he stood up and strode to the podium to deliver his lecture. He spoke of projects finished, those underway, and ones he hoped to tackle in the future. He wished to work on projects that were “neither urban nor rural” but those that occupied a “middle ground.” He hoped to transform workspaces in the strip mall and the office park, to develop multi-use complexes, and, perhaps, have an opportunity to design a church.

Each of these projects would expand his work beyond his portfolio for large corporations and institution by enabling him to reach inhabitants of the work-a-day world. An he planned to continue to design” chairs, tables, rugs, lamps, and silverware.” These are, he stressed, “just a difficult to make (as architecture), but the gratification comes sooner” given the ease and speed of production.

He said “ the brain is a mixing bowl,” and I wonder if he realized that he’d evoked the homely metaphor of the kitchen – the place where so many of his new products resided. He advised students, “to read, to look, to study history, to draw ideas, and to know the language of (contemporary) society” to fill their own mixing bowls. The desire to connect with contemporary society and to meet the needs of everyday client and customers drew Michael Graves out of the ivory tower and into the aisles of Target and JCPenny. His work reflected the eclectic combination of ingredients within his missing bowl of a brain, and his discomfort in emulating a single theory, model, or person enabled him to find delight in aspects of everyday life. His work is an expression of pluralist tendencies at their best.

Return Policy

Our antique/vintage pieces are identified/described and professionally photographed, and considered, “as is”, therefore all sales are final. Read our full refund and return policy.