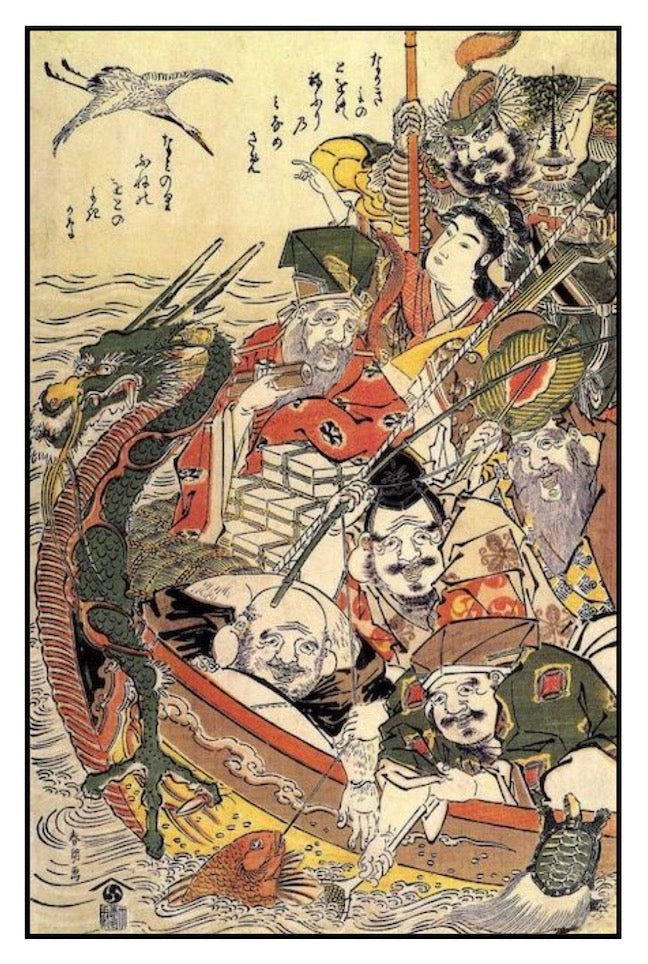

Japan’s Seven Lucky Gods or Seven Gods of Good Fortune, ‘Shichifukujin’, appear as a collection of good-natured and helpful deities. Although worshiped individually in the Japanese tradition, they are now most often shown together in order to multiply their blessings. Each of these Gods began as a more distant figure, until the umbrella of the gods of fortune became more personal and universally accepted. They are now recognized as patrons of specific groups and professions within Japanese society.

These Seven Gods are depicted arriving from heaven into human harbors on the first three days of the New Year on their treasure ship, (Takarabune), bringing gifts for children and good fortune to the older population. A great deal of lore has developed around these seven gods, for which their treasures are said to include a hat and robe of invisibility; an inexhaustible purse of gold; scrolls of wisdom; a divine robe of feathers; as well as jewels and rolls of brocade. Daikoku's mallet, for example it is said to produce gold coins when struck, and Hotei's bag of treasures has valuable objects for special people.

To each of the seven Gods, moreover, particular positive qualities and role have been assigned, so that together they can be seen to form the complete and ideal person. Therefore, their combination is highly auspicious at the New Year. The bright, childlike spirit of the New Year is seen in many comic woodblock prints like the one shown above, of the Shichifukujin, particularly Hotei, whose "bag of treasures" frequently contains laughing children or treasures in other unexpected forms. Quite unlike almighty Gods to be worshipped from afar, the Shichifukujin took an active place in artists prints of daily life, sharing in these everyday activities, and thereby enhancing them.

While the Seven Gods of Fortune are an iconic part of Japanese Folk tradition, their origins are not necessarily from the island nation. The symbolic meanings and physical attributes of the Seven Gods vary slightly, depending on where you are in Japan. Although all are deities of fortune, they also have their own specific domains. They are patrons of specific professions, age groups, and aspirations within society. The number seven is also a lucky number in Japanese culture, giving layers of meaning to the group. Below are traits and a description of each of the Gods:

Benzaiten also referred to as Benten, is the only goddess among the Shichifukujin. She is the goddess of literature, music and femininity. Originally Sarasvati (also Saraswati), the Indian-Buddhist deity of water and creativity, she is often depicted with long, flowing hair and a kimono as well as a Biwa — a Japanese lute. Benzaiten’s places of worship are often located near bodies of water. As well as Enoshima Shrine, she is also enshrined at Inokashira Benzaiten, Banryuji Temple, Fukutoku Shrine and Yoshiwara Benzaiten Shrine.

Bishamonten is the god of warriors and defense against evil, displaying a fierce demeanor, and is nearly always dressed in armor with a weapon in hand symbolizing the sacred sites he protects such as Bishamonten at Zenkokuji Temple, Azabu Hikawa Shrine, Kakurinji Temple and Jindaiji Temple, although the major Bishamon shrines and temples are outside of Tokyo. Chogosonshiji in Nara Prefecture, for example, is said to be where Bishamonten first appeared.

Daikokuten is the god of agriculture, wealth, commerce, and particularly supportive of good luck in careers. He usually has a smile on his face and a big bag of money, and is sometimes pictured holding a magic mallet standing on rice bales. Diakokuten is the other Buddhist deity in the group. Daikokuten is enshrined in many temples and shrines in Tokyo, some famous ones include Sensoji’s Yogodo Pavilion, Daienji Temple and Kanda Myojin Shrine, which has Japan’s largest stone statue of Daikokuten.

Ebisuten is the most well-known among the Shichifukujin, and also the only one of the seven gods with purely Japanese roots. The god of prosperity and fishing, he is the son of the Shinto gods Izanagi and Izanami, the male and female gods of creation. He is represented as a fat, jolly man, holding a fishing rod and a red snapper. Ebisuten and Daikokuten are often presented together, as they are both gods of prosperity. Some places to pay your respect to Ebisuten are Kanda Myojin Shrine, Ryusenji Temple, Suginomori Shrine and Tomioka Hachiman Shrine. There’s also JR Ebisu Stationwhere there’s a statue of Japan’s favorite Shichifukujin.

Fukurokuju is the god of wisdom, health and happiness, Fukurokuju is also an incarnation of the Old Man of the South Pole. He has a long head and long ear lobes and brings along cranes and turtles, both symbols of longevity. Fukurokuju can be visited at Myoenji Temple, where he and Jurojin are enshrined together. You can also find him at Imado Shrine and Sengyoji Temple.

Hoteison is the god of happiness and good fortune, and is thought to have really existed. Originating from Taoist and Buddhist traditions, he is modeled after the Chinese monk Miroku. Represented with a happy face, a bald head and a large belly, Hoteison usually carries a large sack, thought to be a sack of patience. You can pray to be as happy as the god of happiness himself at Hashiba Fudoson Temple, Gokokuji Temple and Zuishoji Temple.

Jurōujin is the god of the elderly, safety, happy living, and longevity. He is portrayed as an old man with a long white beard, who wears a hat and holds a walking stick and fan. He is regularly pictured with a deer that is a symbol of longevity and a messenger of hope. Works of art which are always ink wash paintings are always considered auspicious possessions. Jurōujin can be visited at Myoenji Temple, he and Fukurokuju are enshrined together. You can also find him at Imado Shrine and Sengyoji Temple.