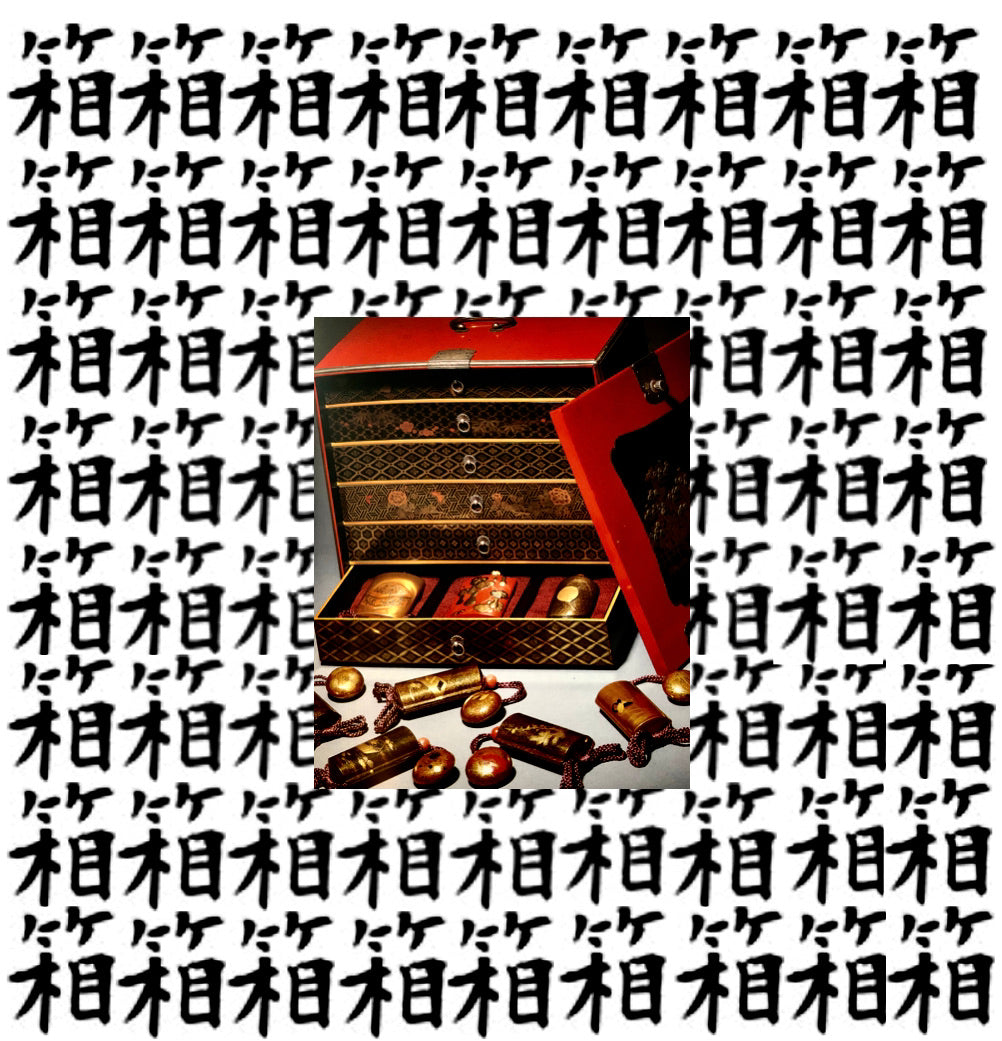

The Box

Firstly, in Japan, the box carries great importance, and is treasured and not to be thrown away. Wrapping and boxing in Japan is a very serious business. The box for most artwork is a work of art in itself, and often has splendid calligraphy written by the artist or maker. A box is made to protect the contents or to keep them in place. Particularly a Tomobako will have a piece of rice paper over it. This is to protect the calligraphy. The box is also protection for the art work, despite the fact that the greatest joy comes from taking the piece out of the box and appreciating it because of the care it has been given.

Boxes can be made of the finest Paulownia also known as Kiri wood. Many boxes have carefully selected tying cord that adds a little class to the package, as well as for keeping the lid in place. Some artists place their stamp on the box for identification. The value of a box, moreover, plays a significant role in determining the price of the contents, particularly if it was signed by the artist vs the apprentice.

The Contents within the Box

Japanese boxes were made to hold all forms of objects and contents, including lunch, writing implements, letters, poems, documents, make-up, hair ornaments, sewing paraphernalia, tobacco, personal drawer container, and herbs/medicine. Also, possessions of traveling samurai, including their armor, nobility possessions, scrolls, paintings, for special occasions, clothing, small sport chests, games, storage boxes for artworks, musical instruments, pottery, peddler boxes for merchants and barbers, money safe, and shoes. Each having their own name identifying the purpose, and in many cases; personalized with decorative motif.

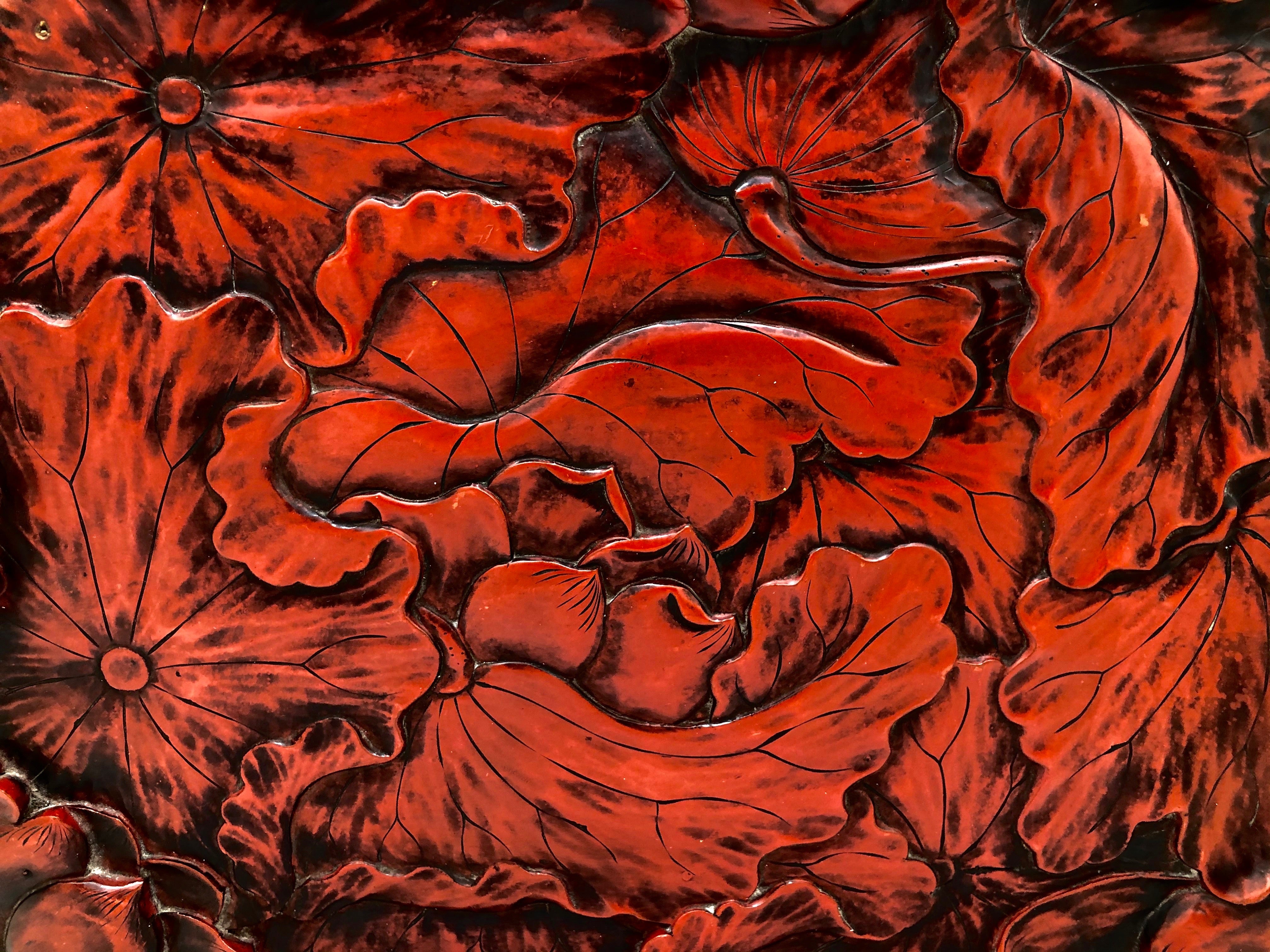

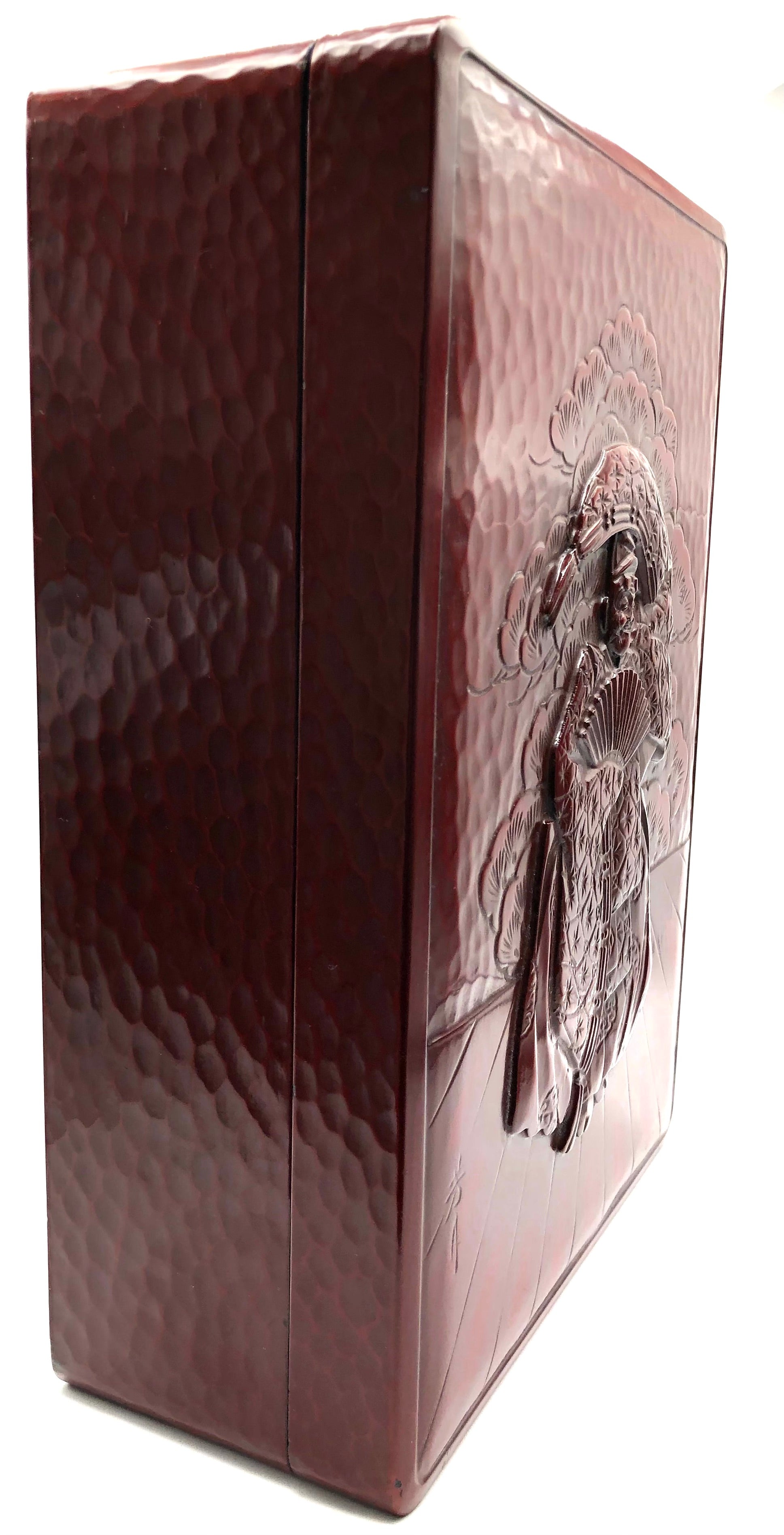

The Japanese were interested in the relationship between humans and nature. They found that harmony could be achieved between contrasting ideas in the world around them. Japanese art, mostly painted decoration, often illustrates this philosophy of harmony through contrasts. Boxes had peaceful nature scenes showing heron, fall grasses and plants, geometric motif and Mon, (family crests), on the outsides or covers. And we cannot leave out wonderful metalwork in the form of hinges, corner protectors, and handles, all individually hand-crafted in an array of materials including bronze, copper, silver, and gold.

Specialized Boxes Used in Japan

Below are a few Japanese names for the boxes used for specific purposes. This does not include furniture, (Tansu), which is also referred to as a box in Japan.

Tomobako, (wooden boxes in which Japanese artworks are stored);

Suzuri-Bako, (for writing implements);

Hakko Bako, (vessels for the prized possessions of traveling samurai and nobility);

Mochi Bako, (for small sport chest);

Ko-Bako, (lacquered box with small drawers);

Kyodai, (vanity Box);

Hasami Bako, (storage/traveling box)

Himitsu Bako, (puzzle box or secret or trick box);

Motoyui Bako, (for hair ornaments);

Gyosho Bako, (peddler’s box for merchants and barbers);

Zeni Bako, (money safe, IOUs, and financial bonds and certificates);

Funa Bako, (ship safe);

Kyodai Bako, (mirror and make-up box);

Haribako, (sewing box);

Tobako-bon, (tobacco box) ;

Yosegi Kobako, (personal drawer box with marquetry);

Gusoku Bitsu, (carrying box for samurai armor);

Fubako, (box for holding letters and documents);

Kotori-Bako, (box for game storage);

Geta Bako, (box chest for shoe storage);

Hon Bako, (for books);

Various craftsmen contributed to the process of making specialized boxes. Skilled workers began by building the core of the box out of seasoned wood, aged for perhaps 50 years. While some craftsmen specialized in cornering and joining the base and sides, others specialized in bent work, creating the thin, rounded sides of the piece. Once the core was complete, the head craftsman who was a skilled artist/craftsman, began the decorative finishing touches, such as lacquer designs. In special cases, they had to build the images from the bottom up, and plan the design for each layer of lacquer ahead of time. In the Edo class system, artisans were ranked third among the four different classes: below samurai and farmers, and above merchants. However, their social status was not reflected in their economic standing. Many artisans commanded a high price for their work, and some were wealthier than those who commissioned them. Japanese artisans were also well respected, which is made evident by the fact that they signed their work.