The waters that surround the islands of Japan and flow from its mountain ranges to form rivers and lakes, host animal life that have sustained humans since prehistoric times. In Japan, Ocean Day, (Umi no Hi), is a holiday to give thanks for the ocean's bounty and to consider the importance of the ocean to Japan as a maritime nation. The ocean provides a rich bounty of food and trade, but also looms as a powerful force that may bring forth terrible destruction, (flooding, mudslides and tsunami). Both these life-giving and life-threatening aspects are part of every citizen’s collective memory, and present a recurring theme in the country’s history, culture, and art.

Utagawa Kuniyoshi’s, Tamatori’s Escape from Ryujin and His Sea Creatures, illustrates the Princess Tamatori, (Tamatorihime), or Ama, and is based around the historical figure Fujiwara no Kamatari (614-649), who was the founder of the powerful Fujiwara clan. Upon Kamatari’s death, the Tang Dynasty emperor, who had received Kamatari’s beautiful daughter as a consort, sent three priceless treasures to Japan in order to comfort his grieving lover by honoring her father. One of these treasures, a pearl, was stolen by the Dragon King in a storm on its way to Japan in the inlet of Fusazaki. Kamatari’s son Fujiwara no Fuhito (659-720) went in search of the pearl to the isolated area where he met and married a beautiful pearl diver named Ama, who bore him a son. Ama, full of love for their son, vowed to help recover the stolen pearl. After many failed attempts, Ama was finally successful when the dragon and other grotesque creatures guarding it were lulled to sleep by music. Upon reclaiming the treasure, she came under pursuit by the awakened sea creatures. She cut open her breast to place the pearl in for safekeeping; the resulting blood clouded the water and aided in her escape. She died from the resulting wound but is revered for her selfless act of sacrifice for her husband Fuhito and their son.

The sea and all of its creatures are the agent of both life and death, the great provider as well as destroyer. The Japanese fishing society respects its power, and live their lives in consonance with its changing tides including depicting folk lore and the battles with what the sea brings forth. For the Japanese, the sea is not just a source of livelihood and sustenance. Like all of nature, it is a dynamic, living entity inhabited by myriad spirits. The Japanese have shrines to honor certain deities of the sea, and their nautical myths and legends are interwoven into their woodblock prints.

Ryūjin, which in some traditions is equivalent to Ōwatatsumi, was the tutelary deity of the sea in Japanese mythology. Ryujin was one of the most important dragons of Japanese mythology. He was the god of the sea that ruled the ocean and protected Japan. He was also the king of all dragons! He was also capable of morphing into different animals as well as taking a human form.

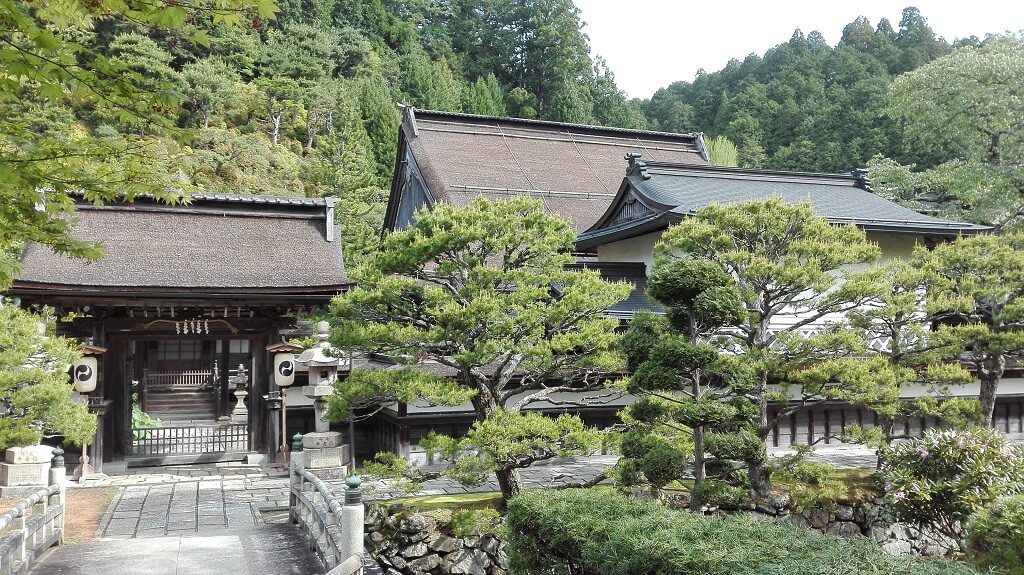

The depths of Lake Biwa, situated in the northeast of Kyoto, is often considered as the home of Ryujin. The dragon lived in Ryūgū-jō, a giant underwater palace. This castle was made of solid crystal as well as red and white coral. The family and faithful servants of Ryujin lived with him in this palace. Sea turtles, fish, octopus and jellyfish were frequently described as the servants of Ryujin. This god of the sea also had shrines all over Japan. Particularly in rural areas where fishing and rainfall were essential for agriculture. These places were also considered to be homes of Ryujin.

With his magical jewels, he controlled the tides and rainfalls. Given how important the sea and fishing was for Japanese people, it is easy to understand why ancestral Japan erected Ryujin as an emblem. Fishermen worshipped the dragon god for successful fishing and calm seas. They celebrated feasts in honor of Ryujin, who was then glorified as the god of the sea.

There were numerous legends around Ryujin, including: The legend of the Flood and the Magic Hook; Urashima Toro the Fisherman, and the Empress Jingu & the Invasion of Korea. Also, the Myth of the Jellyfish to name a few. The Katase-Enoshima station in Fujisawa, was designed with the Ryūgū-jō in mind (Ryujin's palace). These sumptuous architectural buildings glorify Japan's unique culture, customs and traditions, and the importance of the sea and those who made it a part of everyday living.

Ebisu | God of the Sea

If there is anything that the Japanese believe and agree on, it is the firm belief that Ebisu is a native God. Some authorities claim that he is the third child of Prince Isanagi and Princess Izanami, while other say that he is the offspring of the God Daikoku. Further authorities insist that Ebisu was a real person and that his name was Kotoghiro-sushi-no-Mikoto, a man who bore the same name as his father, but for conveniences’ sake, had it shortened to Ebisu.

Ebisu is the God of candor, death, and good fortune, as well as the sea and fish, and whatever his presence was needed some function, he would be looked for near a stream or the seashore where it was certain he would be found. In many pictures and statues of Ebisu, he is shown as a elegantly dressed gentleman wearing formal court garments that are richly brocaded, and incongruously enough, at the same time he is shown carrying a long and clumsy fishing pole and a huge fish called a tai, sea brea), under his arm.

Ebisu is said to have originated the custom of clapping hands before shinto shrines in order to call the attention of the gods to those prayers being offered. Ebisu is said to be the patron of the allied arts, in addition to handling all matters pertaining to the fishing industry, fish restaurant management, fair dealing and the patron of sailors. He is the only God of the seven who has a day held in his honor, and the day called, Ebisu-ko, where special discounts are given at local restaurants and eateries and to avoid punishment from Ebisu, who, it must be remembered is the God of fair dealing, the merchants supplying fish to restaurant would hold these bargain sales as a sort of penance and apology to the God.

The Most Representative Examples of the Sea in Woodblock Prints

Ukiyo-e, often translated as pictures of the floating world, refers to Japanese paintings and woodblock prints that originally depicted the cities' pleasure districts. During the Edo Period the sensual attributes of life were encouraged amongst a tranquil existence under the peaceful rule of the Shoguns. Ukiyo-e prints were often depicted on Japanese screens or scrolls, lending to their narrative feel, and as seen in woodblock prints, these idyllic narratives not only document the leisure activities and climate of the era, they also depict the decidedly Japanese aesthetics of beauty, poetry, and nature both on and off shore.

It would be difficult to discuss Japan’s relationship with the sea without thinking about sea life and how it provided substance throughout the entire islands of Japan. One of the artists that celebrated sea life, and particularly fish, was Hiroshige, in which he celebrated sea life in conjunction with poems on the subject.

Research, (Metropolitan Museum of Art), tells us that Hiroshige made around twenty fish prints beginning in the late 1830s.The first batch of ten were made for the Kyokashi Poetry Guild to complement their writers’ poems, (during the design and printing process, the poets gave their poems to the woodblock carvers, who added the lettering to a block so it would appear on the final print). These prints were said to be made for poets or fans of poetry, because they each contain one or more poems identified in the book Hiroshige: A Shoal of Fishes, which have translations of the poem on the print. Even in these early years of creativity we see many artists collaborating with other disciplines to complete an expression of interests and desires to a shared vision.

Traditional versus Contemporary thought

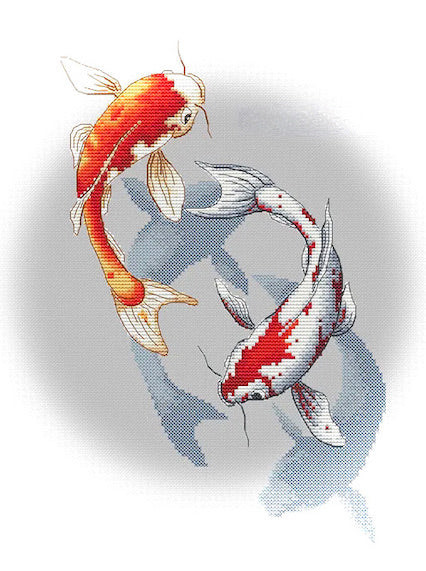

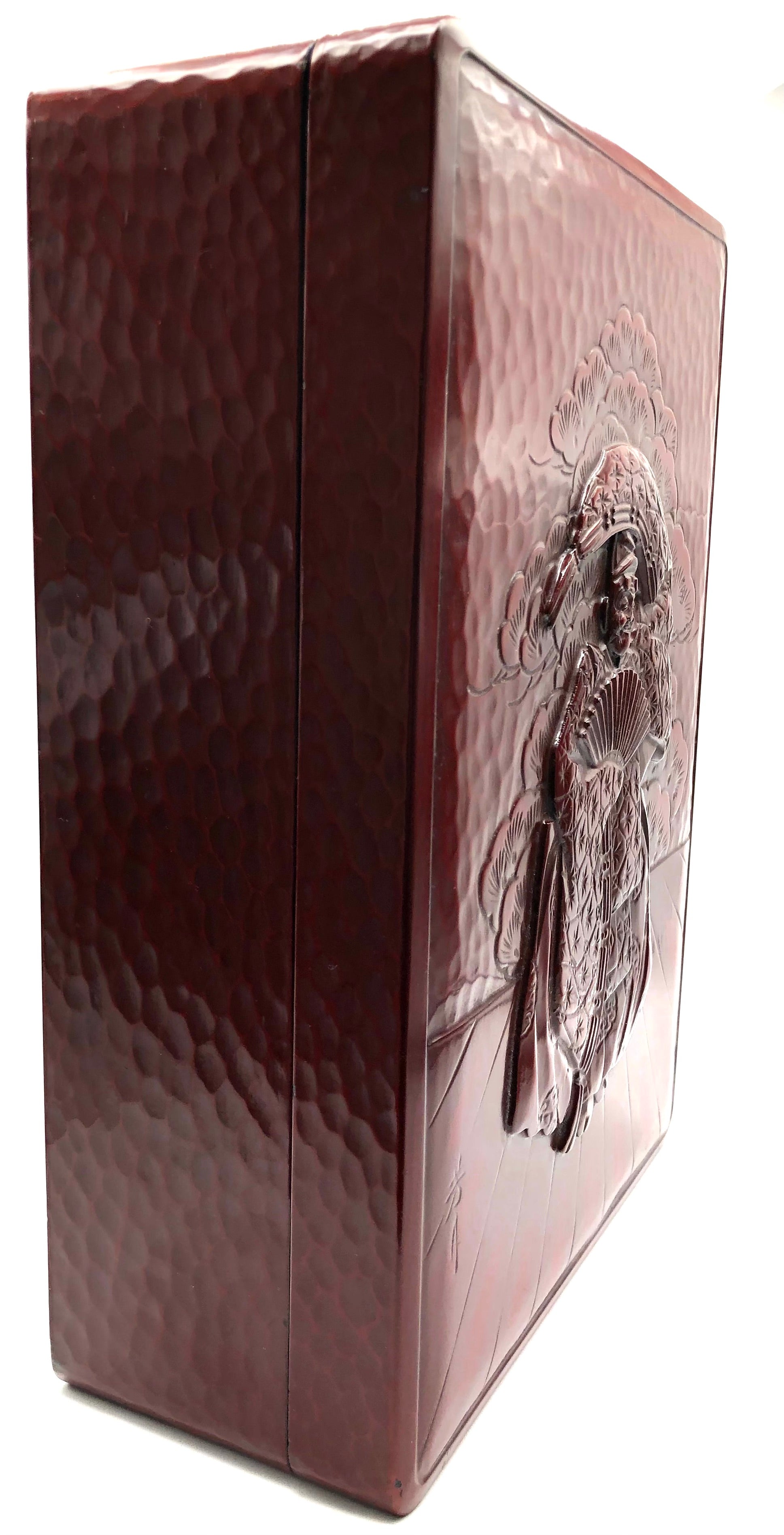

Additionally, we find many forms of aquatic life from artists producing images in multimedia arts. They include paintings, illustrated books, three-dimensional ceramics, wood and lacquer ware, Washi paper lighting, (Andon), fabric for objects such as Noren, (doorway dividers and curtains), including tapestry and textiles for Kimono and Haori. Today, the Japanese appreciation for the beauty and variety of fish and other species is also a subject that is part of the digital media environment such as animation and manga, showing up on giant screens in our streets, screens in commuter trains — the list goes on.

Traditional art work continues to evolve in many forms of artistic expression that complements individual interests in the subject of the animal life around us, and is a reminder that so many species are becoming extinct. The new artwork has evoked many thoughts and discussions on the nature of originality as based work produced in the past. As the art world continues to evolve, so will media, bringing forth new visions of the critical consciousness of artists related to diverse subjects.

The Contemporary Artist | Impressions of Sea Life